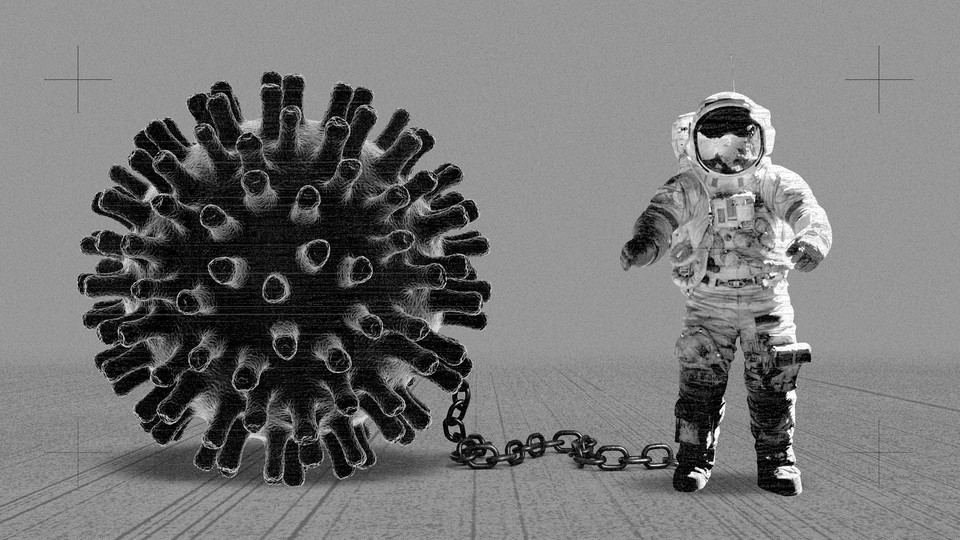

The Pandemic Has Grounded Humankind

Space missions around the world are on hold—a poignant reminder of how COVID-19 has upended civilization.

Last month, as the coronavirus spread largely undetected in the United States, NASA announced it would fund the development of several missions, including to distant moons around Jupiter and Neptune. The missions are meant to bring spacecraft close to alien worlds and draw out the secrets hidden in their depths, to better understand their place in the solar system and, in turn, our own. The space agency gave research teams until November to work on their design concepts for this ambitious project. When I recently asked a scientist on one of the missions about the future of the program, he replied: “Your guess is as good as mine.”

This is one of many disruptions the coronavirus pandemic has brought upon the space industry. Like many other workplaces, space agencies around the world have instructed employees to work from home. A European spaceport in South America postponed all upcoming launches. NASA halted testing on its next big space telescope, which is supposed to launch this time next year. The outbreak helped delay a joint project between the Russian and European space agencies that was supposed to send out a rover to investigate whether life ever existed on Mars. Earth and Mars reach their closest proximity only about every two years, so the rover must now sit in storage until 2022. Even if this world rights itself before then, we still have to wait for the rest of the cosmos to catch up before visiting another one.

Space-exploration delays are a tiny drop in the bucket of cancellations around the world. But they show how the pandemic has upended civilization more clearly than the postponement of important conferences or even the Summer Olympics have. Space exploration has long been seen as a marker of human ambition, a testament to our capacity to think beyond our earthly existence—and then actually loft ourselves toward the skies. As the threat of COVID-19 compels people to stay indoors, it also locks us in our own planet. The coronavirus is here, and we’re stuck with it.

Many spacecraft that have already left Earth are still chugging along, but as the pandemic has worsened, it has forced space agencies to reckon with some difficult questions about how feasible future exploration is right now. Jan Wörner, the director-general of the European Space Agency, told me that he’s prioritizing spacecraft close to Earth, such as the satellites responsible for communication, navigation, and weather observation, which provide far more important services to humanity now than a rover on Mars. Postponing a deep-space mission is disappointing, “but it’s not a catastrophe,” Wörner said. Disruptions to the satellite infrastructure that makes modern civilization possible would be “much more severe.” Because fewer employees are allowed to come into mission control, the agency recently shut off four of its deep-space probes, including two in orbit around Mars and one that just launched last month, bound for the sun.

NASA has had to delay elements of the Artemis program, President Donald Trump’s mission to return Americans to the moon four years from now. The agency has paused production and testing of the mission’s rocket and crew capsule at its facilities in Louisiana and Mississippi, citing the growing number of coronavirus cases in the area.

While some work continues at other sites, the hiatus will make an already ambitious deadline even more difficult to reach. A moon mission doesn’t need a cosmic alignment, but it does need congressional funding, and lawmakers so far haven’t given the Trump administration the lunar budget it wants. Democratic lawmakers, in particular, have been skeptical ever since the administration moved up the mission deadline from 2028 to 2024, the final year of a potential second term for Trump. Whenever we reach the other side of this pandemic, the White House will face an even tougher crowd: How do you convince the public, after society claws its way out of a paralyzing pandemic and a deep recession, that you need their money to send a few astronauts to plant another flag on the moon?

Space travel has always been a hard sell in times of upheaval. Throughout the 1960s, as the country wrestled with the Vietnam War and the civil-rights movement, a majority of Americans didn’t believe the Apollo program was worth the cost, according to polling at the time. Today, NASA’s budget is a fraction of its Apollo-era levels—accounting for less than half a percent of federal spending—but the optics of a mission to the moon, regardless of the price tag, remain delicate.

When I asked NASA leadership whether they had changed their approach to asking for Artemis funding in the midst of the pandemic, I was prepared for the agency’s usual, dreamy remarks about the importance of exploring the great unknown. The answer, while indirect, was more down-to-earth, in keeping with the tone of the times: “NASA space exploration has been an economic driver for the U.S. economy, creating tens of thousands of jobs, reducing our trade deficit, and inspiring countless Americans to pursue careers in STEM fields,” Jim Bridenstine, the NASA administrator, said in a statement. “Artemis will continue that long tradition, growing our economy and improving life on Earth for generations to come.”

It might be tempting, for the science-fiction-minded, to think that global emergencies like this pandemic are proof that space exploration is more worthwhile than ever, because it’s our ticket out of here. But moving a large chunk of humanity off Earth, even if it could be done, would hardly be a panacea. Preparing a passenger ship to Mars under threat of infection would be difficult, and so would preventing the virus from hitching a ride. The International Space Station remains in operation, with three people currently on board—and three more expected to launch in April—but the station is a laboratory, not a disaster bunker.

“It’s just incredibly humbling,” Sara Seager, an astrophysicist at MIT, told me recently. “Because we think we’re so great, right? We can launch all these spacecraft. We’re just so powerful. And now we’re just basically knocked into a standstill.”

Seager works on a NASA mission to detect distant planets outside our solar system, which means she spends her days thinking about worlds beyond Earth. She’s still thinking about exoplanets right now—after all, she still has to work—but like many of us, she is glued to the news, trying to stay healthy, and navigating the strange new norms of everyday life; Massachusetts, where she lives, issued a stay-at-home advisory last week. If some big exoplanet news came out tomorrow, Seager—whom The New York Times once referred to as “The Woman Who Might Find Us Another Earth”—probably wouldn’t pay attention to it. “I don’t think people have the bandwidth to get excited about new discoveries right now,” she said.

Space exploration unfolds over the course of years, even decades; it involves a particular kind of thinking about the future and requires us to imagine separate realities with all the vividness with which we experience our own. It seems almost ridiculous to ask people to consider the cosmic right now, when the “great unknown” can just as easily apply to the next couple of weeks.